Is Freemasonry Esoteric?

Esotericism is a matter of degrees.

By Arturo de Hoyos, 33°, Grand Cross | Grand Archivist & Grand Historian |Some people consider Freemasonry inherently esoteric, while others think the Craft is a fraternity celebrating friendship and mutual support.

Is Freemasonry esoteric, or not? The short answer is “Yes, no, maybe.” Esotericism is any topic “intended for or likely to be understood by only a small number of people with a specialized knowledge or interest.” This certainly applies to Masonry. But on a deeper level, and in a Masonic context, the word esoteric is usually taken to mean that our ceremonies and rituals allude to realities and/or truths not generally understood, or which may have a spiritual component to them. The term is tainted to some people, and acceptable to others; hence, it may not be easy to wholly accept or discard the term “esoteric Masonry.” Like an onion, each esoteric layer successively builds upon the other. We can all agree that Masonry is intended to be understood by few, and that it’s a kind of specialized knowledge.

But the questions are, “What kind of specialized knowledge?” and “Are they real secrets?” Depending upon one’s inclinations, the Master Masons Degree has been interpreted in a variety of different ways by different persons. For some, it’s a story of fidelity; for others, it teaches hope in the immortality of the soul; for still others, it’s a lesson in alchemy; and yet for still others, it alludes to the discovery of entheogens. Some see it as multi-faceted, or a combination of various things. But, as I have written elsewhere, we should avoid trying to enshrine our preferred interpretations as the “true” one.

Since 1717 there have been over 1,000 “Masonic” degrees created. The most popular survived and are included in many of the rites, orders, and systems we know today. Like a meal, each degree is only as good as its creator. A recipe may include many of the same ingredients as other meals, yet taste completely different. Similarly, we may see many of the same “ingredients” (features) in a number of degrees which teach completely different things. The predilections of a degree’s author affect the content as much as the taste buds of a chef. Anyone who has traveled a bit can tell you that even the “flavor” of the foundational degrees (Craft/Blue Lodge Masonry) can differ immensely from state to state, and more so if you compare these degrees across the Scottish Rite, York Rite, Swedish Rite, R.E.R., or something else. In the “higher degrees,” the differences are even more dramatic and pronounced: some are philosophical, others practical; some present allegory, and others offer discourses on symbolism or (quasi-)historical themes. In something like the Scottish Rite, the same degree may have dramatically different rituals, depending upon the jurisdiction (compare, for example, the Southern Jurisdiction with the Northern Masonic Jurisdiction: the 20th Degrees are nothing alike).

When someone describes himself as an “esoteric Mason” it often means that he perceives, and embraces, what appear to be aspects of the “Western Esoteric Tradition” in our rituals; i.e., some affinity to the symbolism of Hermeticism, Gnosticism, Neoplatonism, Kabbalah, etc. Freemasonry is an eclectic organization and, at various times, we have borrowed the language and symbols of these and other traditions. The question is, do our rituals really teach these things as realities or do we use them to stimulate thought—or both? As we are told in the 30°, Knight Kadosh, we should not mistake a symbol for the thing symbolized. In some cases, I believe that is what has happened, while in others, I believe we do indeed have vestiges of other traditions. But even when they are there, they may be only one layer thick on our Masonic onion.

The problem is twofold: some deny any esoteric influences at all (or assert they are just used symbolically), while others claim it’s the main part of the onion. If the matter is open to interpretation (not defined by the ritual itself), who has the “right” to decide?

This much we know: many of Freemasonry’s symbols were used before the modern fraternity existed (1717), and they appeared in a variety of books. Some were in educational and philosophical texts, and others in Hermetic or alchemical works. Consider, for example, a 1615 engraving by Gabriel Rollenhagen, in which a woman holds a square, accompanied by the motto Serva Modum, “Keep in Measure” (i.e., square your actions). The image (below) was redrawn and appeared in Choice Emblems, Divine and Moral, Antient and Modern (London: 1732).

The term is tainted to some people, and acceptable to others; hence, it may not be easy to wholly accept or discard the term “esoteric Masonry.” Like an onion, each esoteric layer successively builds upon the other. We can all agree that Masonry is intended to be understood by few, and that it’s a kind of specialized knowledge.

But the questions are, “What kind of specialized knowledge?” and “Are they real secrets?” Depending upon one’s inclinations, the Master Masons Degree has been interpreted in a variety of different ways by different persons. For some, it’s a story of fidelity; for others, it teaches hope in the immortality of the soul; for still others, it’s a lesson in alchemy; and yet for still others, it alludes to the discovery of entheogens. Some see it as multi-faceted, or a combination of various things. But, as I have written elsewhere, we should avoid trying to enshrine our preferred interpretations as the “true” one.

Since 1717 there have been over 1,000 “Masonic” degrees created. The most popular survived and are included in many of the rites, orders, and systems we know today. Like a meal, each degree is only as good as its creator. A recipe may include many of the same ingredients as other meals, yet taste completely different. Similarly, we may see many of the same “ingredients” (features) in a number of degrees which teach completely different things. The predilections of a degree’s author affect the content as much as the taste buds of a chef. Anyone who has traveled a bit can tell you that even the “flavor” of the foundational degrees (Craft/Blue Lodge Masonry) can differ immensely from state to state, and more so if you compare these degrees across the Scottish Rite, York Rite, Swedish Rite, R.E.R., or something else. In the “higher degrees,” the differences are even more dramatic and pronounced: some are philosophical, others practical; some present allegory, and others offer discourses on symbolism or (quasi-)historical themes. In something like the Scottish Rite, the same degree may have dramatically different rituals, depending upon the jurisdiction (compare, for example, the Southern Jurisdiction with the Northern Masonic Jurisdiction: the 20th Degrees are nothing alike).

When someone describes himself as an “esoteric Mason” it often means that he perceives, and embraces, what appear to be aspects of the “Western Esoteric Tradition” in our rituals; i.e., some affinity to the symbolism of Hermeticism, Gnosticism, Neoplatonism, Kabbalah, etc. Freemasonry is an eclectic organization and, at various times, we have borrowed the language and symbols of these and other traditions. The question is, do our rituals really teach these things as realities or do we use them to stimulate thought—or both? As we are told in the 30°, Knight Kadosh, we should not mistake a symbol for the thing symbolized. In some cases, I believe that is what has happened, while in others, I believe we do indeed have vestiges of other traditions. But even when they are there, they may be only one layer thick on our Masonic onion.

The problem is twofold: some deny any esoteric influences at all (or assert they are just used symbolically), while others claim it’s the main part of the onion. If the matter is open to interpretation (not defined by the ritual itself), who has the “right” to decide?

This much we know: many of Freemasonry’s symbols were used before the modern fraternity existed (1717), and they appeared in a variety of books. Some were in educational and philosophical texts, and others in Hermetic or alchemical works. Consider, for example, a 1615 engraving by Gabriel Rollenhagen, in which a woman holds a square, accompanied by the motto Serva Modum, “Keep in Measure” (i.e., square your actions). The image (below) was redrawn and appeared in Choice Emblems, Divine and Moral, Antient and Modern (London: 1732).

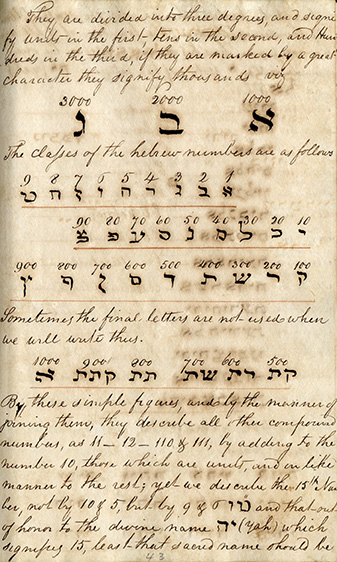

Certainly, there are clear examples of “borrowings” from “esoteric” texts. A version of the 14°, Grand Elect Perfect and Sublime Mason (as it was then called), used by the Supreme Council of Charleston from about 1801–22 (below), includes a portion of a lecture on Hebrew numerology, or gematria, extracted from Cornelius Agrippa’s De Occulta Philosophia (1531–33). If asked if that degree were esoteric, I would say “yes,” while to its counterpart in a later version or in another Supreme Council, I would say, “no.”

Certainly, there are clear examples of “borrowings” from “esoteric” texts. A version of the 14°, Grand Elect Perfect and Sublime Mason (as it was then called), used by the Supreme Council of Charleston from about 1801–22 (below), includes a portion of a lecture on Hebrew numerology, or gematria, extracted from Cornelius Agrippa’s De Occulta Philosophia (1531–33). If asked if that degree were esoteric, I would say “yes,” while to its counterpart in a later version or in another Supreme Council, I would say, “no.”

My point is to quit quibbling over such things, and find the common ground where we “can best work and best agree.” If esotericism interests you, that’s fine; if not, that’s also fine. My personal library is well-stocked with enough material on both sides to make anyone think in favor of, or against, virtually any position. The important thing is to be well-educated, and understand what we know first. Before you reach for the stars, make sure your feet are firmly planted on the ground. Make yourself into someone who can be taken seriously. Learn the facts about our origins based upon what we know.

I sometimes speak about “historical records” versus “hysterical documents.” Before you buy into such fantasies as “Freemasonry descended from the ancient Egyptians,” get a quick education. Here are three books to give you a reality check: (1) Harry Carr, World of Freemasonry; (2) Bernard E. Jones, Freemasons Guide and Compendium; (3) David Stevenson, The Origins of Freemasonry: Scotland’s Century 1590–1710. When you can speak intelligently about the Old Charges (Gothic Constitutions), early Freemasonry in Scotland, the formation of the first Grand Lodge, and how and when the degrees developed, people may be inclined to listen to you, when you start to talk about more exotic things. Educate yourself well enough to argue both sides of the argument.

Take due notice thereof and govern yourselves accordingly.

My point is to quit quibbling over such things, and find the common ground where we “can best work and best agree.” If esotericism interests you, that’s fine; if not, that’s also fine. My personal library is well-stocked with enough material on both sides to make anyone think in favor of, or against, virtually any position. The important thing is to be well-educated, and understand what we know first. Before you reach for the stars, make sure your feet are firmly planted on the ground. Make yourself into someone who can be taken seriously. Learn the facts about our origins based upon what we know.

I sometimes speak about “historical records” versus “hysterical documents.” Before you buy into such fantasies as “Freemasonry descended from the ancient Egyptians,” get a quick education. Here are three books to give you a reality check: (1) Harry Carr, World of Freemasonry; (2) Bernard E. Jones, Freemasons Guide and Compendium; (3) David Stevenson, The Origins of Freemasonry: Scotland’s Century 1590–1710. When you can speak intelligently about the Old Charges (Gothic Constitutions), early Freemasonry in Scotland, the formation of the first Grand Lodge, and how and when the degrees developed, people may be inclined to listen to you, when you start to talk about more exotic things. Educate yourself well enough to argue both sides of the argument.

Take due notice thereof and govern yourselves accordingly.

This essay originally appeared in the March/April 2017 issue of The Scottish Rite Journal—available online and via the free app for Apple and Android devices, just visit your preferred app store and search “Scottish Rite Journal.”

Image Captions/Credits: Detail of the front cover of the March/April 2017 Scottish Rite Journal. Illustrations: (left) E. B. MacGrotty, 33°, from A. de Hoyos, Albert Pike’s Esoterika (Washington, DC , 2008); (right) from J. Stöffler, Künstlicher Abmessung aller Grösse (Frankfurt am Main, 1536) Serva Modum, “Keep in Measure” (Square your actions). From Choice Emblems, Divine and Moral, Antient and Modern (London: 1732). Ordini dritto e giusto, “Ordered Right and Just.” From Cesare Ripa, Nova Iconologia (Padua: 1618). A page from a version of the 14°, Grand Elect Perfect and Sublime Mason (as it was then called), used by the Supreme Council of Charleston from about 1801–22. (All graphics courtesy the Archives of the Supreme Council, 33°, SJ, USA.)