By Paul Rich, 32°

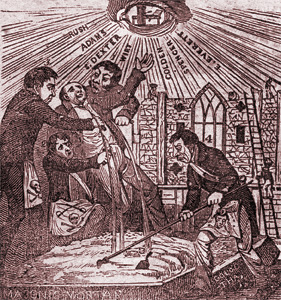

Photo: The New England Anti-Masonic Almanac for 1835 luridly depicts the abduction and murder of William Morgan in 1826.

Freemasonry was booming in America in the 1820s when suddenly anti-Masonic hysteria gripped the country. Why did such promising times for Freemasonry so quickly become the worst of times, a nightmare of persecution? Part of the answer can be found by examining thoroughly the reaction to the 1825 tour of the Marquis de Lafayette,1 a shrewd suggestion made by historian Mark Tabbert in American Freemasons: Three Centuries of Building Communities. Lafayette was received by the Masons in most of the towns he visited and welcomed as one of the last living friends of George Washington and one of the last living heroes of the American Revolution. The extravagant Masonic-led affection for a foreign aristocrat could be regarded as something conspiratorial. For some, Bro. Tabbert writes, displays of mysterious aprons and jewels along with the whispered reference to “the Brotherhood,” “heightened suspicion of the craft as an international order with secrets and a radical revolutionary past.”2

While manifestly great Masonic things were being done in Washington, D.C., where the lodges were prospering, 1826 was also the year when William Morgan, a miscreant living in upstate New York who had threatened to expose secrets of the Craft, allegedly was murdered, firing a national hysteria that imperiled Freemasonry in the United States.3 Bro. Arturo de Hoyos in his monumental study of Masonic exposés, Light on Masonry, remarks about Morgan, “He had never been initiated into Masonry, and his entire Masonic experience was built upon deception.”4 However, the incident ignited a conflagration. “Masons’ disproportionate share of positions of political leadership most rankled and concerned incipient Anti-Masons.”5

Anti-Masonry for the moment was well organized and successful.6 Lodges in the District of Columbia lost members and some were shuttered such as Columbia Lodge in 1835. Naval Lodge reportedly met secretly in the home of the commandant of the Navy Yard.7 The new Central Masonic Hall was lost to creditors, and the Medical College Building had to be used for meetings. A decided low came in October 1834, when Federal Lodge No. 1 voted to disband. To his credit, the Master, Clement T. Coote, who was also the Grand Master, would have none of it and put off that action, but two years later, Coote and seven others were all that were left of Federal; on November 17, 1837, the charter was temporarily returned to the Grand Lodge.

But while the anti-Masonic movement hurt the Grand Lodge and some individual lodges, the Grand Lodge of the District of Columbia did not suffer as much as other grand lodges. “The agitation which convulses the North did not pass the Potomac,” remarked Chief Justice and Brother John Marshall in 1833.8 (Marshall was Past Grand Master of Virginia.) In fact, Potomac Lodge No. 5 attributed a momentarily increased membership to curiosity that the anti-Masons provoked. Extinction of Freemasonry in Washington was never a prospect. What is noteworthy is that right in the midst of all the turmoil, so many courageously public Masonic functions took place.9

By no means did the Washington Masons hide themselves. A notable event during the troubles had been on January 4, 1830, when Brother Andrew Jackson, President of the United States, Brother John H. Eaton, Secretary of War, and Brother William T. Barry, Postmaster General, were elected honorary members of Federal Lodge. In 1831 the Grand Lodge was invited to assist in the ceremonies for an addition to the Capitol. Cornerstone were laid in 1833 for the United German Church at 20th and G Streets Northwest and for the Methodist Church on 9th St. Despite the furor, the Grand Lodge and its officers were not afraid to be seen in public. And in time, the Anti-Masons lost their audience and the Craft recovered.

Endnotes

1. Compare Lloyd Kramer, Lafayette in Two Worlds, (Chapel Hill and London: Univ. of N.C. Press, 1996), 189.

2. Mark A. Tabbert, American Freemasonry: Three Centuries of Building Communities (New York and London: N.Y. Univ. Press, 2005), 57.

3. While a majority believe that Morgan was killed by Masons, the evidence is not entirely conclusive, and there remain, “two conflicting explanations of the fate of William Morgan; the one, that under pressure, he consented to leave the country and with five hundred dollars in his pocket, deserted his family, yielded to his new sense of freedom, probably shipped in the crew of some vessel at Montreal, travelled from shore to shore until his end came. The other, that he was brutally murdered; his weighed body thrown into the Niagara River.…” John C. Palmer, “The Morgan Affair and Anti-Masonry”, Little Masonic Library (Richmond, Va.: Macoy Publishing & Masonic Supply, 1946), 2:180. Compare Mitch Horowitz, Occult America (Bantam Books 2009), 27–29.

4. Arturo de Hoyos, Light on Masonry: The History and Rituals of America’s Most Important Masonic Exposé (Washington, D.C.: Scottish Rite Research Society, 2008), 36.

5. Kathleen Smith Kutolowski, “Freemasonry Revisited: Another Look at the Grass-Roots Bases of Antimasonic Anxieties,” R. William Weisberger et al. eds., Freemasonry on Both Sides of the Atlantic (Boulder, Co.: East European Monographs, 2002), 592.

6. Joel H. Silbey, The American Political Nation (Stanford, Ca.: Stanford Univ. Press, 1991), 18.

7. But Harper writes, “The anti-Masonic wave which swept over the country in the thirties, engulfing and destroying many organizations of the Craft, seems not to have disturbed the serenity of Naval Lodge. It is perhaps worthy of remark that tradition affirms that for a period of months during the excitement the Lodge met secretly in the quarters of the Commandant of the Navy Yard, but no confirmation of the story can be found in the records and it is only given as of interest in showing the troubled character of the time.” Kenton Harper, History of Naval Lodge No. 4, F.A.A.M. (Washington, D.C.: Naval Lodge, 1955), 33.

8. Steven Bullock, Revolutionary Brotherhood (Chapel Hill, N.C. and London: Univ. of N.C. Press, 1998), 310.

9. See James Van Horn Melton, Rise of the Public in Enlightenment Europe, (Cambridge: Univ. of Cambridge Press, 2001), 4.

Editor’s Note: This article is from a work in progress on the history of Freemasonry in the District of Columbia.