By Adam G. Kendall, 32°

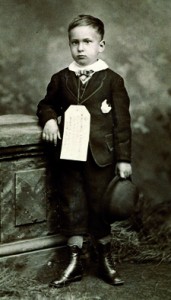

Photo: A widely distributed staged photograph of Walter Wilcox, with a tag around his neck (not the original) depicting the identification card he wore during his journey across the country. This photograph was sold for $1.00 in order to raise further funds for his care. (All Photos: Henry Wilson Coil Library and Museum of Freemasonry, Grand Lodge of California, F.&A.M.)

In October 1878 Walter Cary Wilcox was about 4½ years old, alone, and orphaned. His mother was dead by yellow fever, and his father had died from injuries sustained in a steamship accident a few years earlier when Walter was five months old. During the final years of the 1870s, New Orleans, like most of the South, was ravaged by the epidemic. While Walter contracted the fever and eventually recovered, his mother lost her battle.

Walter’s late father, Henry E. Wilcox, had been a Mason in New Orleans, and his mother had been employed to care for a dying Mason, James Pratt, in Florida. Her care endeared the Wilcox family to the Masons of a Chicago lodge that was later to play a hand in assisting Walter during his trip west. Discovering that Mr. Pratt was a Mason, Mrs. Wilcox personally had arranged for his remains to be sent back to his mother lodge in Chicago for a Masonic funeral service. For this, his lodge, Garden City No. 14, sent her a gold watch in gratitude. She and young Walter then set out to return to New Orleans.

Misfortune was to again overtake the tragedy-stricken family after returning to Louisiana. Soon a mother was dead and her child bereft. Those who were arranging for the mother’s burial discovered the watch and its Masonic-related engraving and directed the case to the Masons in New Orleans and their grand lodge.

Now it was October 3, 1878, and Walter sat on a train with a packing ticket tied around his small neck inscribed with a message entrusting him to the care of the brotherhood and perfect strangers while he made his way from Louisiana via Louisville and Chicago, and then on to Oakland in order to live with his grandmother, Mrs. Hannah Cary.

Upon his arrival in Sacramento, the youngster was met by a large contingent of Masons including the Grand Master of California, Nathaniel G. Curtis, who reportedly hand-carried the road-weary and weakened Walter from the train. The crowd met their interest with an outpouring of gold coins intended for his immediate welfare. Walter was thence conveyed again by locomotive to Oakland accompanied by William Knox and Mrs. William Petrie (wife of William Petrie, Past Grand Commander of California, Knights Templar, and then-Grand Bible Bearer of the Grand Lodge). Walter had yet another identification tag placed around his neck, this one bearing the seal of Sacramento Commandery No. 2, Knights Templar. Meanwhile, Alexander Abell, Grand Secretary of the Grand Lodge, had been in previous communication with Walter’s grandmother. He arranged for the boy to become a ward of the Grand Lodge, F. & A.M. of California, and to receive a sum of $600 for his first year in California with portions to be disbursed $25 per month. His previous plight and new presence in the state was well noted and hundreds of his posed photographs entitled “The Mason’s Boy”, or “The Mason’s Orphan” became extremely popular among the fraternity. In addition, articles in newspapers and Masonic publications along with the California Grand Lodge Proceedings told his story.

But his journey was not to end there. In 1880 Walter became seriously ill with the measles and had to leave the state with his grandmother in order to be cared for by friends. However, her means were extremely limited—even for travel on an “emigrant train” [sic]. The efforts of Nathan W. Spaulding, Grand Treasurer from 1885–92, appraised A. N. Towne, General Superintendent of the Central Pacific Railroad, of the boy’s continuing dilemma. Towne generously donated two first class tickets for Walter and his grandmother and ensured their return trip by notifying his colleagues in the Union Pacific, Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroads. During Walter’s recovery in Ohio in 1881, Grand Secretary Abell wrote to him:

I am glad to see you write that you are a “Mason’s Boy”, and I hope that when you grow up to be a man you will be a good Mason and try to help other Mason’s little boys. With much love, your affectionate friend.…

Grand Lodge records and personal letters attest to the annual disbursals for Walter’s care until his grandmother died in 1888. Touchingly, it was found that instead of spending the money the Grand Lodge had given her, she had put it all away as a trust for her grandson’s education.

Naturally Walter had made life-long friendships with the men who ran Grand Lodge, and it was Nathan Spaulding who would formally adopt Walter and raise him as his own son. In Walter, Spaulding found an intelligent but untrained mind—owing to his frequent illnesses he had missed much school. Nevertheless, over time Walter improved and became a model pupil. During a period in American history with so much insecurity and pain, it is always refreshing to witness a happy ending: the efforts of the Grand Lodge and the love of the Fraternity arrived with manifold blessings in that Walter grew up well adjusted and loved. Through Masonic assistance he procured work in the auditing department at Wells Fargo & Co. and upon reaching majority age was made a Freemason, eventually taking his very well attended Third Degree on May 11, 1895, at Oakland Lodge No. 188 (now Oakland-Durant-Rockridge Lodge No. 188). Later, Walter pursued a career in dentistry and had a practice in Stockton. In 1901, both he and his wife, Jeanette, were listed as members of Homo Chapter No. 50, Order of the Eastern Star in that city, although his later years were spent in Fresno where he died on December 11, 1952.