By Michael A. Halleran, 32°

Illustration: Ted Bastien, 32°

Date: December 20, 1898

Weather: Cold

Outlook: Snow

Mrs. Hartman1—a skeptic in all things, or nearly all—surprised me at dinner last Wednesday by producing two tickets to that peerless magician Harry Kellar on Saturday at the Grand Theatre!

“Will you come with me?” she inquired earnestly.

“Of course,” I said without hesitation. “You know how much these conjurers fascinate me, and Kellar is the very best of the lot. But I am surprised you wish to go. You have on more than one occasion decried them all as fakes … or worse!”

“That is why I have procured seats in the very front row—so that I might discern the deception with my own eyes!” she laughed coquettishly.

Saturday arrived, with her looking fetching, and we were escorted to our seats in the very front row—they must have cost a small fortune—as we were barely five feet away from center stage. Evelyn Mrs. Hartman, armed with two opera glasses (“in case he might make one disappear” ) could scarcely contain her excitement at the prospect of discovering the great man’s secrets.

Directly he appeared and started the show with an impressive display of sleight-of-hand, producing colored ribbons and flowers—a veritable garden—from a silk hat as well as various other bits of hand magic—all very entertaining. He gave a short exposé on turning a silk handkerchief into an egg—showing a hollow egg with a hole in the side. At this my dear companion exclaimed “Aha!” rather too loudly when she gathered how it was done, only to have the magician confound her by doing again, but this time breaking the egg open and pouring out yolk and white into a champagne goblet!

Following intermission, during which I had to be particularly vigilant that Mrs. Hartman didn’t slip backstage to conceal herself in the scenery, Kellar unveiled “the Marvelous Hindoo clock”—a baffling affair that answered questions (so long as they could be divined by numbers) by means of its minute and hour hands. And not staged questions, either, but proper ones solicited from the audience. It told birthdates, the years of great battles, and even the year of an old coin (1871) that Mrs. Hartman pressed into the magician’s hand. At this she admitted that it was utterly impossible anyone could have known the answer, and I confessed that I was mystified as well.

By the end of the show she was cheering like a Grenadier Guardsman very loudly indeed.

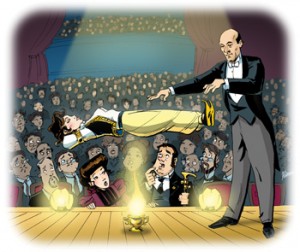

The levitation trick was particularly good—I’d seen it before in St. Louis. His assistant, a young girl in oriental costume, was by various gesticulations placed in an hypnotic spell. Her body became rigid and then she slowly arose—suspended in midair—floating ethereally off the stage for several minutes! Kellar produced a wooden hoop and circulated it through the audience—I handled it myself and could find no void or artifice in it whatsoever, and Evie Mrs. Hartman would barely hand it back, so intent was she to discover any hidden mechanism. He passed this hoop over and under his somnolent assistant to prove that she was not suspended by wires or similar apparatus. Then with a few incantations and more gesticulations, she descended slowly to the stage and awoke—a fascinating illusion, indeed!

After the finale, the crowd insisted upon an encore. At this, the great man emerged and announced that he would perform “the Ring Trick,” which I had heard of before but never witnessed. A few weeks before I had given Mrs. Hartman a ring as a love token of my admiration devotion esteem. A Masonic signet ring that I often wore on my little finger—I had it resized for her hand and to my delight, she wore it always. When the magician asked for ladies’ rings, she practically threw it at him, so great was her excitement. When he had gathered half a dozen, he loaded them into an ancient horse pistol and uttering various incantations, fired it into a box a few yards off at stage left. Upon opening the box, each of the rings were there, fastened with a ribbon to a flower! A remarkable trick to be sure, but even more remarkable was Mrs. Hartman’s exclamation on the carriage ride home.

“Hiram Mr. Brother! This is not your ring!”

“How do mean?”

“Well, I’ve only just removed the ribbon and the flower; I didn’t look at it very closely when he gave it back to me, but this is most certainly not your ring—it’s far too large!”

And deuced if she wasn’t right. It was a Masonic signet to be sure, much like mine, but clearly sized for a masculine hand—not resized for my dearest’s her delicate finger. In addition, there was a Spanish inscription—Paz, Bem-estar e Fraternidade2—inside the band. I asked if she would let me take it to lodge on Monday to try to find out more about it, and possibly locate its owner, and with a goodnight kiss she consented.

This evening at lodge, I was again at the Tyler’s station. The master had just signaled his intent to open the lodge, and as I fastened the outer door, a brother appeared whom I did not recognize. I told him quietly that he would have to wait to be examined before I could admit him.

“Alas,” he replied, making the sign of a M.M., “I am not here to attend lodge, but rather to make amends for a terrible mistake.”

This puzzled me and I told him so.

“You will recall,” he said mysteriously, “on Thursday night, I mistakenly returned my ring instead of returning yours to your beautiful companion. You’ll admit they are very similar,” he added with a slight smile.

“By Jove, Sir,” I exclaimed, pumping his hand like the town well, “Why, you are the great Kellar himself! I had no notion you were a Mason!”

He gave me an unmistakable fraternal grip, and produced my ring with a low bow—“My train leaves this evening—may I trouble you for my ring? I am rather attached to it, despite its tendency to slip from my finger at odd moments.”

“Of course, of course,” I said, and retrieving it from my waistcoat pocket. I was just about to invite him in—damn the examination! when the deacon’s rap sounded on the outer door, demanding a reply. “Pray excuse me for one moment,” I said and hurried to the door, answering in like manner the order from within. “However did you know where to find me?” I said on turning around.

But he had vanished!