The Three Rings of Lessing: A Representation of the Masonic Ideal of Tolerance

By Mark Dreisonstok, 32° • Staff Writer/Editor

An important figure in German Freemasonry is Gotthold Ephriam Lessing (1729–1781). Though today remembered more as an essayist, critic, and theorist, Lessing was by profession a dramatist whose works are performed in German-speaking countries even today. Lessing is best known within Masonic literature for his authorship of Ernst und Falk, a philosophical dialogue between Falk, a Mason, and Ernst, a non-Mason. There Lessing writes lines often quoted in German Masonic circles: “Freemasonry is nothing arbitrary, nothing superfluous. Rather it is something necessary, which is grounded in the nature of man and civic society. Consequently one must also be able to chance to think of it just as well through his own meditation as guided to it by instruction” (Lessing’s Masonic Dialogues; A. Cohen, trans., 1927, p. 26). This combined focus on the twin Masonic ideals of inner personal development and outward commitment to education and civic engagement makes it clear why Lessing—like many figures of the German Enlightenment—was drawn to Freemasonry. The Lennhoff and Posner’s International Freemasons Lexicon (1932) gives the dates for Lessing receiving his three Masonic degrees as “between August 10 and September 24 1771” at the Three Golden Roses Lodge in Hamburg.

Lessing’s most popular work dealing with Masonic/Enlightenment themes is not, however, Ernst und Falk but rather Nathan the Wise, a play which Mackey’s Encyclopedia of Freemasonry (1912) terms “vigorously Masonic” Although Nathan does not make explicit reference to Freemasonry or Masonic symbolism, it represents a crucial aspect of the German Masonic movement of the eighteenth century: religious tolerance, a key theme in light of the relatively recent and devastating European Wars of Religion. The play is set in Jerusalem in 1191, during the Crusades, an era replete with religious warfare between Christians and Muslims, with Jews caught in between. The ruler is the historical Sultan Saladin, one of the protagonists in this Enlightenment drama. Interestingly, in Albert Pike’s Magnum Opus (1857) version of the 29°,“Grand Ecossais of St. Andrew,” Saladin is presented positively as the “king of kings” who exhibits tolerance and ensures safe conduct to a brave Christian knight that he may return “with sufficient escort, after he hath eaten with us, to the Christian army.” Lessing similarly endows Saladin with a nobility of spirit.

By the end of Nathan, we learn that Recha, raised Jewish, is actually a blood relation of Saladin, and a Christian Templar Knight is later revealed to be her brother. (We should not be surprised that there is a Templar Knight here, for Lessing notes in Ernst und Falk that “the Knights Templar were the Freemasons of their time!”) The characters thus represent the three Abrahamic faiths—the main religions known well in Europe at that time—quite literally, and, by the end of the play, all embrace.

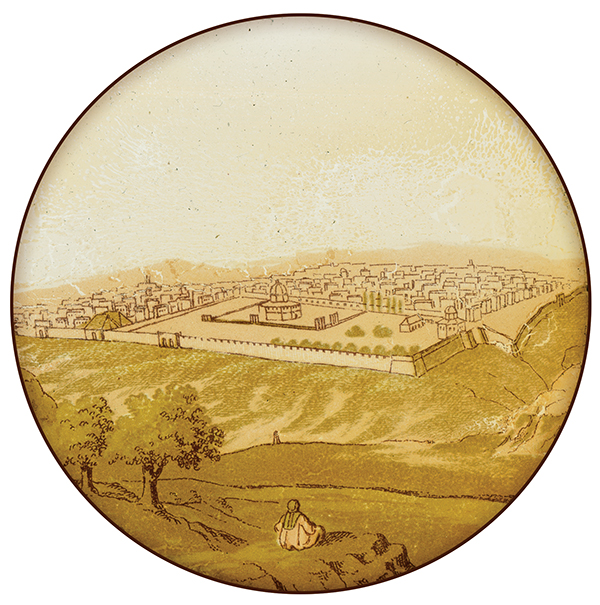

(Above) The slide has what appears to be an original label marked “Jerusalem.” (From Patmos-Solomon’s Lodge No. 70, Savage, MD)

This reconciliation comes about partially by way of a story within the play involving three rings. Nathan, a Jewish merchant who has a reputation for wisdom, has been called to the palace of the Sultan, for the Muslims at this point rule Jerusalem. Nathan assumes that Saladin is calling him to his palace in order to borrow money from him for the wars—then, as now, wars were expensive! As his audience with Saladin enfolds, however, Nathan realizes this is not the reason for the summons. Saladin’s reason rather is to ask Nathan, a man known for his perception, a question: “What is the true faith?” Nathan, perhaps suspecting a trap, answers diplomatically with a parable involving three rings—a parable so Masonic in character that the Three Rings became a name given to many Lodges and to at least one Masonic periodical (Mackey, Encyclopedia).

“In days of yore,” the parable begins in the almost biblical verbiage of translator R. Dillon Boylan, “there dwelt in Eastern lands a man who from a valued hand received a ring of priceless worth. An opal stone [of] ever-changing hue.” The ring was not only beautiful; it also held the power to make its wearer beloved by both God and men. This ring was passed down in the family generation to generation. It was always willed to the son in the family deemed “best” in terms of both ethics and love. The ring finally came down to a man who had three sons he loved equally. The father promised the ring to each son, convinced during his private conversations with each that, at that moment, that each was the one truly deserving of the ring. To solve his dilemma, he ordered two rings made exactly like the first and which were such perfect imitations they could not be told from the original.

The father gave these rings to his three sons privately and then passed away. When the three sons realized that each had “the ring” they quarreled and, in a part of the story which perhaps sounds rather modern, took the matter to court to resolve! The judge first raises the possibility that perhaps all three rings are false and the original has been lost. However he then suggests a happier option, one which can solve the problem empirically: each son should wear his ring, and the one who displays the most virtuous qualities will prove his possession of the real ring!

The three rings are, of course, emblems of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In telling his parable, Nathan is saying that each religion is a “brother” to the other, having descended from the moral tradition of the patriarch Abraham. Further, adherents to these faiths should treat one another with mutual respect and display the virtues of their “ring,” rather than vying for dominance in court per the parable, or by slaughtering one another in the battlefields of the historical Crusades.

In this way, Lessing encourages the Enlightenment and Masonic ideal of tolerance which today is a relevant and vitally necessary message to a world weary from religious strife.

This article originally appeared in the July/August 2019 Scottish Rite Journal, pp. 10–11

Featured image: An opal ring from the House of the Temple Library & Museum's collection